Mike James is a photographer and digital artist. He’s a dog whisperer (they don’t listen) and a cat herder (where’d they all go). He is the managing principal of TB&O, a studio that’s been in continuous operation since 1971 serving up clients with product imagery. More than 100,000 images served. Under Mike’s leadership, the studio has evolved from principally providing traditional photography to offering photo-real rendering, animations and creating interactive web experiences. The client base is international which makes Mike a world traveler as well. Mike’s newest favorite expression, is “Render ’til your fingers blister.” Which is sorta gross, but descriptive of the passion the TB&O team has for creating great imagery.

Mike James

What sparked your interest in Photography?

A friend of mine and I attended the Nikon School when we were 11. Then I traveled the streets of San Francisco shooting anything and everything. I did my own developing as a kid. So, photography is something I got interested in a long time ago. It kept me on the streets instead of off the streets, but out of trouble. Mostly. Over the years my interest has never waned because there is always something new to try. I love to see what other people are doing and that often can inspire a new idea or direction.

What led to the inclusion of CGI?

Ah, yes, CGI. We often joke that we were really doing CGI before there was CGI. Back when we started with Photoshop, we were doing so much to refine our imagery that I think it qualified as rendering. That aside, the transition from film to digital and then to rendering from computer models seems like a natural progression to me (especially after I experienced how easy it was to get results from KeyShot).

Ah, yes, CGI. We often joke that we were really doing CGI before there was CGI. Back when we started with Photoshop, we were doing so much to refine our imagery that I think it qualified as rendering. That aside, the transition from film to digital and then to rendering from computer models seems like a natural progression to me (especially after I experienced how easy it was to get results from KeyShot).

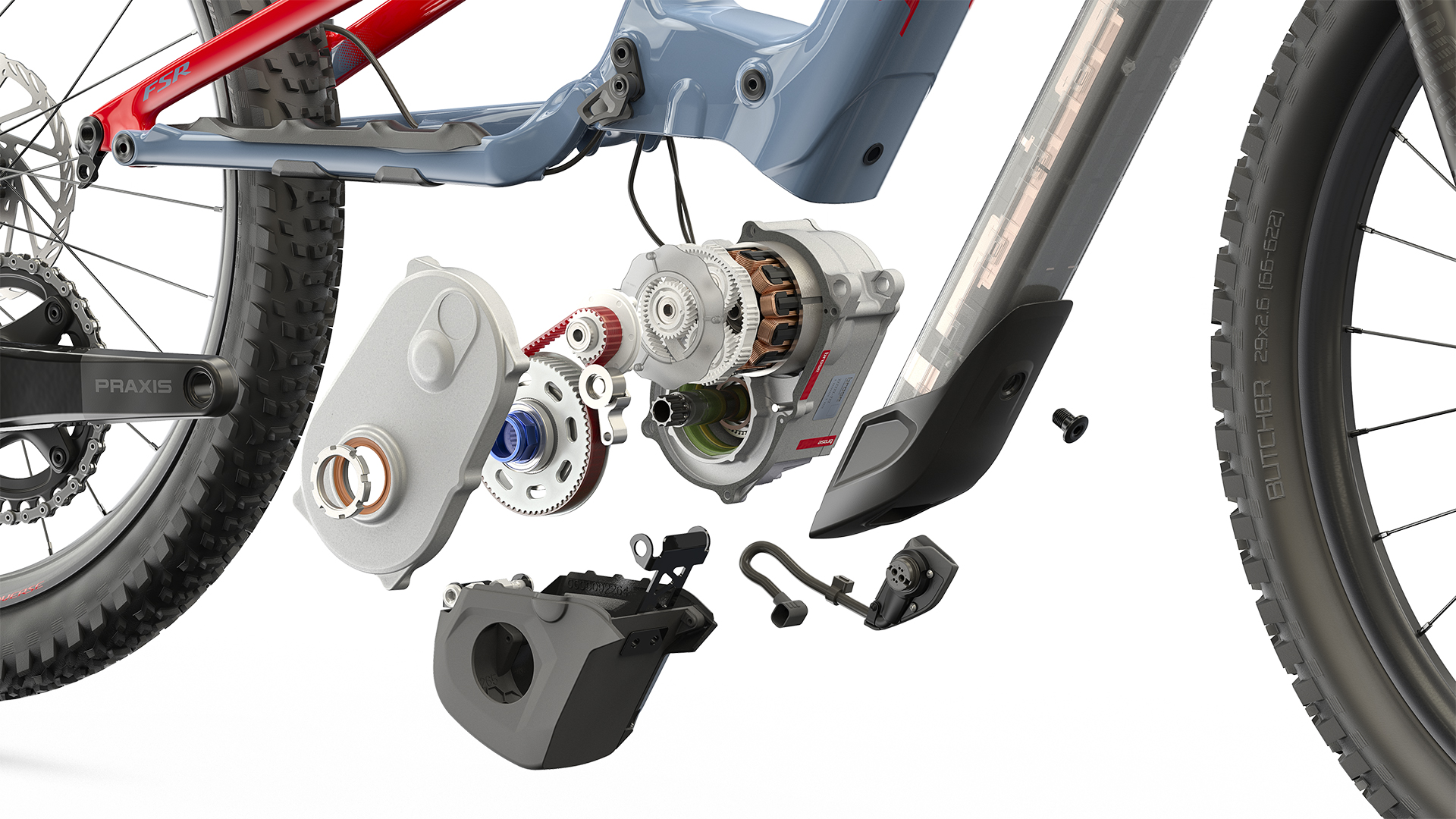

Motorola was a client for 13 years before Google acquired them. They insisted on traditional photography. Their lawyers drove that decision because of their interpretation of what constitutes truth in advertising. But, we had this one large project where the Motorola product team was having trouble getting the samples from China to look the way they wanted. During several of the conference calls the Industrial Designer was using KeyShot for his presentations.

On one call we suggested that we take his KeyShot files and render all the shot angles and lighting. We’d then get the team to approve everything and when the samples arrived we could shoot and produce final images much faster. Everyone thought this was a good idea. Except our team; we had never really used KeyShot. As I’ve been prone to do, it was more or less a case of opening my mouth before thinking. There was a little bit of stress but we learned quickly how powerful and easy KeyShot was for a photographer to use. Doing it this way saved the project from going off the rails.

How has photography and the business of photography changed over the years?

The transition from film cameras to digital cameras in phones is obviously huge. Everyone has a camera in their pocket every day and all the time. Traditional camera companies are pulling out all of the stops to maintain sales. Because. The best camera is the camera you have with you. The quality of phone camera for posting images on the Internet has made everyone a photographer. But on a broader level, I think of the progression of photography as similar to printed books. In the old days, the typeface, its size, the spacing of characters and lines were all critically important to the readability of words on a page. Publishers paid attention to the minute nuances of typographic details. Today, all we care about is whether something is legible. We’ve come to accept the lowest common denominator of mediocrity. We’re in the same place with photography. But, I’m a positive person–really, I am!

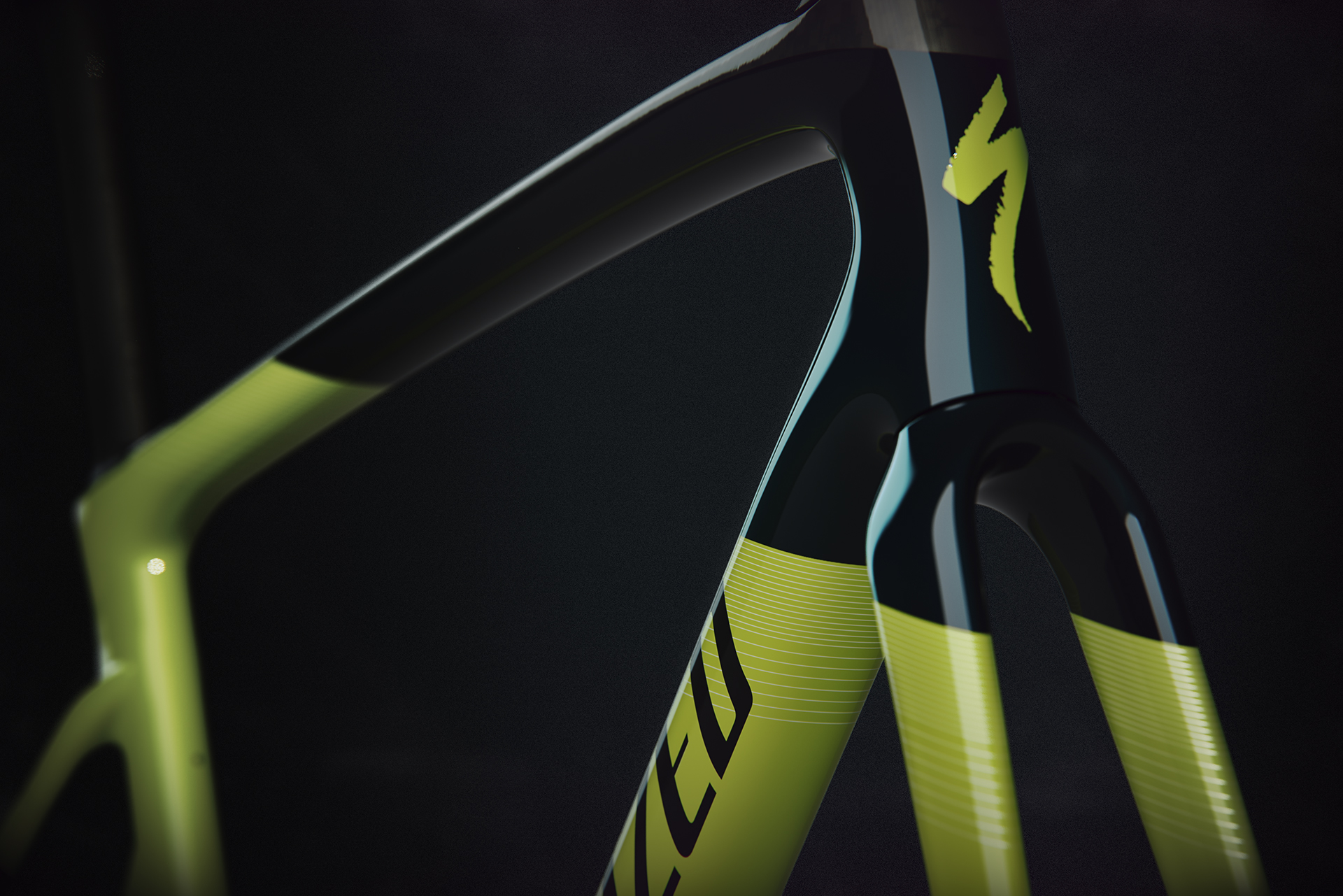

Our studio has always been about the detail of our craft and creating the finest product photography possible. When the studio opened in 1971, we used film. Today, we use advanced digital capture devices to create traditional images. And, we use KeyShot to render absolutely photo-real images from computer models. In either approach, it’s the devil that is in the detail. I like to point out that when we photograph something we work really hard in post to get all the scratches, dust and imperfection off the product. When we render, we put dust, scratches and imperfections in to add “realism.” What a world this is.

One of the things that most excites me about the photography space today is the renewed interest in film. I jumped on the Polaroid Impossible Project bandwagon when they launched their efforts to remake Polaroid film. In many ways going back to Polaroid film or any film frees up your mind. The result won’t be as sharp. The film can’t even begin to compete with the dynamic range of digital. These things and others could seem like a negative. Like having to wait to develop the film! But, for me it shifts my thinking to the art of the image. This renewed interest in film means that manufactures are slowly rethinking how to make some of the old classics. I hope I see the day that Kodachrome returns! I’m also bullish about black and white. Most of my personal photography is black and white. It’s where I started. And, again, it just frees my mind of color clutter and lets me focus on tone and shapes and textures. Sadly, I haven’t been able to convince any clients that shooting their product in black and white will sell more.

What is unique about your approach to a project?

If I need to net out what is unique about how we do what we do, I’d say it’s that I’m a photographer. That means we apply the same approach we do if we are shooting something on the set in the studio. We’re different because we understand composition; we know way too much about the nuances of lenses; we’ve grown up with all sorts of different light sources; and, we’ve become very tuned to how various types of light behaves with different materials. Everyone in the studio comes from a background of photography. They learned to render, model, UV map, etc. after they learned to set a light and click a shutter.

What is your primary 3D modeling software?

So in the studio, we use SOLIDWORKS. In hindsight, I wished we’d made other choices. But, in reality, most of our models come from our clients. When we do need something special, we do it in SOLIDWORKS. Or, often it’s the case that we reach out to the artist network that we have under NDA. We’ve had great success working with folks we’ve met in the KeyShot community.

I am a closet renderer. Tim Feher taught me to be that. He’d call me up on the weekend and ask me what I’m doing. I’d tell him I was working on a vintage motorcycle. And, he’d say, “In KeyShot?” And, I’d have to fess up that I was in the garage with real oil on my hands and grease under my nails. Tim can be tenacious. So, I started taking other people’s models and rendering. For fun. Tim and I teamed up one Christmas break several years ago and rendered a car together. The idea was to go from KeyShot “clay” to heroes and detail shots. After the holiday, we published a daily newsletter, for about two weeks, that had a new image each day of the progression from “clay” to finished hero shots (see the results here). Collaborating and learning from Tim was fun (and relieved the stress of the holidays).

What perspective could you provide for 3D professionals?

What is important to me in a model is accuracy to the real thing. I discard a lot of models after comparing them to reference images because the detail is missing or wrong. In my opinion, when you’re rendering something, especially something historic, the first thing that gives credibility is accuracy. And, I’d be remiss at an epic level if I didn’t point out how important it is to me to be able to smooth parts to a level that I am embarrassed to admit. I’ll spend a pretty penny for a model by someone who cares about the details the way I do.

Where in the process do you use KeyShot?

For us, we use KeyShot in the front end of a project. Many of our projects are renders and then animations or interactive web experiences. So, KeyShot is the front line tool for us. Our animation sequences get put together in other software (mainly After Effects) and our stills get post in Photoshop at least 99.9999% of the time (give or take).

What makes KeyShot an important tool to have?

KeyShot, to me, is like a cork is to a wine bottle. Well, that’s weird. But, I’ll stand by it because any wine needs a cork and we really wouldn’t be rendering at the level we are without KeyShot. If I was into tattoos, I’d have a KeyShot tattoo somewhere you wouldn’t want to see. That might be the wine talking. Bottom line is, really, the power of the KeyShot Material Graph. When I first saw the Material Graph, I had almost no idea what I was looking at. Now, most of my dreams are about material graphs or wandering through the nuances of a very complex material graph. Weird, I know. #donthate

What advice would you give to someone interested in doing what you do?

Whoa! Hold up there. Don’t even think about it. Go into banking or real estate or Ponzi schemes. But, if you’ve got your heart set on being a modeler or a visual artist, then become a photographer first. Really. The fundamentals of photography are so important to every decision we make in KeyShot. And, if there is one sub-discipline in particular, it’s light and how it behaves. I remember when I first started doing photography commercially my partner tried to convince me that I would eventually walk into a room and size up the light before I saw the people. I wasn’t buying it. I thought that was nutzo. But, I’ll be a monkey’s uncle if that isn’t the case. And, sadly, this fact alone is why I am seldom the hit of the cocktail party. Or, really any party.

And, then there is this piece of advice, worth every penny, wait for it… Pick your software and get really, really, really good at it. It’s not the tool, it’s what the artist does with the tool. Lots of people will try to convince you that their tool is better. It’s not the tool that makes you good, it is how darn good you are with your tool. But, as tools go, and I’m not getting paid for this, KeyShot can make you look really, really good. Except on dating sites. For that you need Photoshop. Probably.

One last question: why do you always say, “we?”

I seldom work alone. My best work is almost always the result of collaboration with our folks in the studio (primarily). We’re a team. I hate it when people try to spell team with an “I.”